ICAO CORSIA Update: Compliance Complexities Under ICAO’s New Carbon Offsetting Scheme

Republished in "The Air & Space Lawyer" and "Green Air Online" in April 2019

Airlines and airline associations have broadly welcomed ICAO’s new carbon offsetting scheme, scheduled to commence on January 1, 2019. However, the scheme’s Standards and Recommended Practices (the SARPs) impose an immediate compliance obligation on international airlines and raise a number of potential risks for aircraft financiers and lessors.

In June 2016, the 39th Assembly of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) agreed to adopt a global market-based measure to control aviation carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions,1 This scheme is referred to as the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). On June 27, 2018, ICAO’s Council adopted the First Edition of Annex 16, Volume IV, which details the international SARPs for CORSIA.2 Ultimately, over 700 aircraft operators3 (Operators) worldwide will be compelled to comply with various aspects of the scheme.

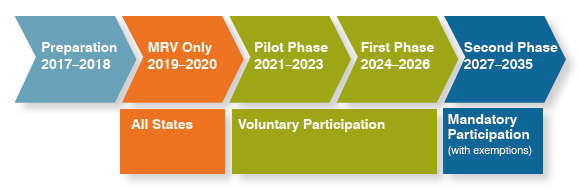

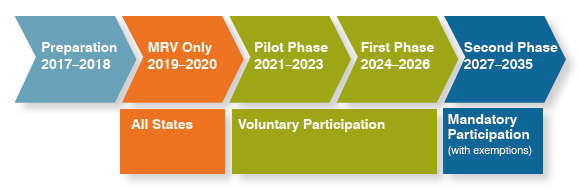

Commencing on January 1, 2019, all Operators not otherwise exempt from CORSIA4 with annual emissions exceeding 10,000 metric tons of CO25 will be required to record and report emissions data for their international flights on a yearly basis. Operators will also be required to submit an emissions monitoring plan by February 28, 2019. Annual emissions reports and Emissions Monitoring Plans must be submitted by an Operator to its ICAO Contracting State6 regulator even if the Contracting State has opted not to participate in the voluntary phases of CORSIA. The reported data will form the baseline for calculating compliance requirements during the upcoming voluntary and compulsory phases of the scheme occurring during the periods indicated in the following timeline:

CORSIA timeline – Under the Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV Only) Phase (2019–2020), all aircraft operators are required to submit an Emissions Monitoring Plan7 no later than 28 February 2019 and report their 2019 and 2020 emissions to their ICAO state regulator by 31 May 2020 and 31 May 2021 respectively.

Given these impending deadlines, from a practical standpoint, Operators need to be well into the process of developing and implementing their international aviation emissions monitoring plans in order to ensure compliance.

ICAO expected most of its 192 Member States to implement the SARPs into their respective national laws without modification. CORSIA Contracting States were given until October 22, 2018 to file disapproval of the SARPs8 and were also required to file any differences to ICAO in transcribing the SARPs into their national laws by December 1, 2018. On November 21, 2018, the EU Council instructed EU Member States to file differences to ICAO concerning the lack of time available to transcribe the SARPs into EU law and also that certain differences currently exist between EU Directive 2003/87/EC and detailed rules adopted by the EU Commission, on the one hand, and CORSIA, on the other hand, particularly with respect to MRV requirements and to offsetting requirements.9 This has created widespread concern that the SARPs will not be universally adopted, transcribed or fully implemented by each Contracting State. This could potentially result in a patchwork of different sub-rules, regulations and enforcement measures that may apply, and some Contracting States may even simply fail to adopt, regulate and/or enforce CORSIA at all.

CORSIA therefore raises a number of potential and unforeseen credit, political and reputational risks, not only for Operators but also for aircraft owners10 and lessors. ICAO has yet to determine the types of carbon offset units that will be eligible under the scheme and whether grandfathering of existing offsets will be permissible.11 Any restriction concerning the type or vintage of eligible offsets may increase the cost of compliance and thus create an economic burden for many Operators under CORSIA. The expected bottom-line impact of CORSIA compliance for airlines has caught the attention of international credit rating agencies such as Moody’s, who suggested in a recent report that

“[g]rowing carbon offset costs have the potential to become significant relative to operating profit…carbon costs have the potential to lower operating income by between 4% and 15% by 2025, and by between 7% and 35% by 2030, all else being equal.”12

CORSIA compliance will present aircraft owners with several commercial and legal risks and challenges. One such challenge is identifying who will be responsible for compliance under the scheme where the operator of a flight has not been identified. The first line of inquiry is the ICAO designator,13 followed by the aircraft registration mark and holder of an Aircraft Operator Certificate (AOC). If the ICAO designator and AOC holder cannot be readily established, CORSIA compliance will then will fall to the aircraft owner identified in the aircraft registration documentation.14 Should an Operator fail to submit an emissions monitoring plan and annual emissions reports, its CORSIA Contracting State may not be able to identify the operator of an aircraft’s international flight activity or, consequently, the responsibility for its emissions from such activity, and therefore CORSIA compliance obligations would automatically be attributed to the aircraft owner. Any such risk may become compounded for aircraft lessors and investors in asset-backed finance portfolio transactions.

The fact that ICAO has no legal rights to enforce the CORSIA SARPs creates risk that local governments and regulators may hold an aircraft owner responsible for CORSIA non-compliance. Each individual Contracting State is responsible for transcribing CORSIA into its domestic law. While it remains unclear as to exactly how (if at all) and when each Contracting State will do so, the possibility certainly exists for states to pass laws allowing relevant government entities to impose a lien on, and seize and potentially sell, an aircraft pending cancellation of sufficient emissions offsets for the operator’s entire fleet—similar to the Eurocontrol fleet lien and applicable regulations in certain jurisdictions under the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS)—notwithstanding the rights of the aircraft owner or mortgagee.15 In addition, legal and financial consequences may arise should an Operator fail to cancel a sufficient quantity of eligible emissions offset units to cover its existing obligations following an insolvency declaration.

Furthermore, current lease and loan documentation practices need to be reconsidered in light of the differences between compliance under EU ETS and compliance under CORSIA. EU ETS runs on an annual reporting and emissions allowance surrender cycle. In contrast, while CORSIA will have an annual emissions reporting cycle, cancellation of emissions unit offsets will, starting in 2020,16 be subject to a three-year compliance cycle. This longer cycle is likely to cause aircraft owners to accumulate a much greater credit risk exposure. Requiring an Operator, as a condition precedent under a lease or loan agreement, to deliver a CORSIA “Letter of Authority” permitting the relevant regulator to disclose the Operator’s emissions obligations as a means for a lessor or mortgagee to monitor this credit exposure will likely have little if any effect. It is presently unknown to what extent, if any, Contracting State regulators will honor such letters of authority, as CORSIA allows aircraft Operators to request regulators to keep commercially sensitive emissions data confidential.17 Moreover, until the end of the three-year compliance cycle expires, the CORSIA regulator will not be able to confirm the level of an Operator’s compliance and financial liability, by which point the damage (and potential exposure for the lessor or mortgagee) may be irreversible. Also, the price of eligible emissions units under CORSIA (measuring the cost of compliance) will not be known until the time of purchase by the Operator, unless an Operator hedges its CORSIA exposure through a forward contract with a carbon broker.

Should the EU decide to transcribe CORSIA18 as an annex to EU ETS, then the existing enforcement measures for non-compliance, being a statutory penalty of €100 per ton of CO219 plus additional local fees, penalties and the rights of aircraft seizure, detention and sale may apply. Meanwhile, the UK is scheduled to exit the EU ETS in March 201920 and is currently considering its options, including whether to seek to negotiate with the EU to opt back into EU ETS, or alternatively set up its own ETS or UK aviation carbon offset scheme for domestic and intra-European Economic Area (EEA) flights. The UK remains fully committed to CORSIA for international flights outside the EEA. Meanwhile, the uncertainties surrounding CORSIA could create challenges in disclosing climate change-related risks, trends or factors in publicly listed leasing and finance company annual financial reports21 and offering memoranda for securitization transactions that require a credit rating.22

In sum, given the plethora of potential risks and uncertainties under CORSIA, it is important that aircraft owners and financiers understand the basic functions of the scheme, keep an eye on the evolving landscape of requirements and consequences of non-compliance, and consider implementation of risk mitigation measures in lease and loan documentation. While there is considerable momentum for commencing and implementing CORSIA as a global method for reducing aviation emissions, the scheme still presents many unknowns and risks, but few clear solutions.

Vedder Price can advise on developing CORSIA-related provisions in aircraft lease and loan agreements. Avocet Risk Management is positioned to provide CORSIA risk management and mitigation solutions to aircraft owners and financiers.

- 1See https://www.icao.int/Newsroom/Pages/Historic-agreement-reached-to-mitigate-international-aviation-emissions.aspx.

- 2 See https://www.unitingaviation.com/publications/Annex-16-Vol-04/#page=1.

- 3 ICAO’s CORSIA uses the term “Aeroplane Operator.”

- 4 Operators subject to CORSIA’s technical exemptions being those (i) with annual emissions of less than 10,000 t/CO2, (ii) operating humanitarian medical and firefighting flights, (iii) operating military and State flights (Presidential, customs, police etc.), and (iv) operating helicopters.

- 5 10,000 metric tons of CO2 is approximately equivalent to 4,000,000 liters (1,000,000 US gallons) of JET-A aviation fuel. Source UK Department of Transport.

- 6 The terms “Contracting State” and “Member State” are used interchangeably by ICAO.

- 7 An “Emissions Monitoring Plan” is a collaborative tool between the state and the aircraft operator that identifies the most appropriate means and methods for CO2 emissions monitoring on an operator-specific basis, and facilitates the reporting of required information to the state.

- 8 The first edition of ICAO’s SARPs (Annex 16, Volume IV), was adopted on June 27, 2018. Such parts of the SARPs that are not disapproved by more than half of the total number of Contracting States on or before October 22, 2018 became effective on that date and will become applicable on January 1, 2019.

- 9 http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14330-2018-ADD-1/en/pdf.

- 10 CORSIA uses the term “Aeroplane Owner” as the scheme is only applicable to fixed wing aircraft and excludes rotor wing aircraft.

- 11 Particularly Carbon Reduction Emissions offset units created under the United Nations’ Clean Development Mechanism See Moody's “Passenger Airlines—Global: Pricing power, route mix to determine credit implications of carbon transition” (April 2018). https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-Carbon-transition-risk-varies-by-airline-with-international-carriers--PR_382486?WT.mc_id=AM%7eRmluYW56ZW4ubmV0X1JTQl9SYXRpbmdzX05ld3NfTm9fVHJhbnNsYXRpb25z%7e20180418_PR_382486.

- 12 Being the three (3) letter call sign, should the aircraft operator have such a call sign. See clause 1.1.3 of the CORSIA SARPs, https://www.unitingaviation.com/publications/Annex-16-Vol-04/#page=1

- 13 See clause 1.1.4 of the CORSIA SARPs, https://www.unitingaviation.com/publications/Annex-16-Vol-04/#page=1.

- 14 For example, under the UK’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Regulations, the UK Civil Aviation Authority has the right of seizure, detention and sale of aircraft in the event of persistent EU ETS aviation non-compliance. However, liens are not applicable where an aircraft is owned by a lessor and liens are not transferable to a new operator of an aircraft subject to penalties (i.e., “follow the metal”).

- 15 The first CORSIA emissions credits are scheduled to be cancelled on January 31, 2025.

- 16 ICAO’s SARPs (Annex 16, Volume IV) Chapter 2.3.16/2.3.17.

- 17 Depending on whether the EU considers that CORSIA meets the terms of Bratislava Declaration.

- 18 EU Directive 2008/101/EC, includes provision of an excess emissions penalty of EUR 100 applies for each ton of carbon dioxide equivalent emitted for which the aircraft operator has not surrendered allowances. Payment of the excess emissions penalty does not release the operator or aircraft operator from the obligation to surrender an amount of allowances equal to those excess emissions when surrendering allowances in relation to the following calendar year. Potentially a similar penalty regime may also apply for CORSIA.

- 19 But will require aircraft operators reporting to the UK regulator to continue to comply with EU ETS for the 2019 emissions compliance year.

- 20 At least 40 countries, including all EU Member States currently have mandatory emissions reporting programs in place, World Resources Institute, https://www.wri.org/blog/2015/05/global-look-mandatory-greenhouse-gas-reporting-programs.

- 21 Credit risk arising from CORSIA should be a factor in future rating agency modelling.

Vedder Thinking | Articles ICAO CORSIA Update: Compliance Complexities Under ICAO’s New Carbon Offsetting Scheme

Newsletter

December 12, 2018

Republished in "The Air & Space Lawyer" and "Green Air Online" in April 2019

Airlines and airline associations have broadly welcomed ICAO’s new carbon offsetting scheme, scheduled to commence on January 1, 2019. However, the scheme’s Standards and Recommended Practices (the SARPs) impose an immediate compliance obligation on international airlines and raise a number of potential risks for aircraft financiers and lessors.

In June 2016, the 39th Assembly of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) agreed to adopt a global market-based measure to control aviation carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions,1 This scheme is referred to as the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). On June 27, 2018, ICAO’s Council adopted the First Edition of Annex 16, Volume IV, which details the international SARPs for CORSIA.2 Ultimately, over 700 aircraft operators3 (Operators) worldwide will be compelled to comply with various aspects of the scheme.

Commencing on January 1, 2019, all Operators not otherwise exempt from CORSIA4 with annual emissions exceeding 10,000 metric tons of CO25 will be required to record and report emissions data for their international flights on a yearly basis. Operators will also be required to submit an emissions monitoring plan by February 28, 2019. Annual emissions reports and Emissions Monitoring Plans must be submitted by an Operator to its ICAO Contracting State6 regulator even if the Contracting State has opted not to participate in the voluntary phases of CORSIA. The reported data will form the baseline for calculating compliance requirements during the upcoming voluntary and compulsory phases of the scheme occurring during the periods indicated in the following timeline:

CORSIA timeline – Under the Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV Only) Phase (2019–2020), all aircraft operators are required to submit an Emissions Monitoring Plan7 no later than 28 February 2019 and report their 2019 and 2020 emissions to their ICAO state regulator by 31 May 2020 and 31 May 2021 respectively.

Given these impending deadlines, from a practical standpoint, Operators need to be well into the process of developing and implementing their international aviation emissions monitoring plans in order to ensure compliance.

ICAO expected most of its 192 Member States to implement the SARPs into their respective national laws without modification. CORSIA Contracting States were given until October 22, 2018 to file disapproval of the SARPs8 and were also required to file any differences to ICAO in transcribing the SARPs into their national laws by December 1, 2018. On November 21, 2018, the EU Council instructed EU Member States to file differences to ICAO concerning the lack of time available to transcribe the SARPs into EU law and also that certain differences currently exist between EU Directive 2003/87/EC and detailed rules adopted by the EU Commission, on the one hand, and CORSIA, on the other hand, particularly with respect to MRV requirements and to offsetting requirements.9 This has created widespread concern that the SARPs will not be universally adopted, transcribed or fully implemented by each Contracting State. This could potentially result in a patchwork of different sub-rules, regulations and enforcement measures that may apply, and some Contracting States may even simply fail to adopt, regulate and/or enforce CORSIA at all.

CORSIA therefore raises a number of potential and unforeseen credit, political and reputational risks, not only for Operators but also for aircraft owners10 and lessors. ICAO has yet to determine the types of carbon offset units that will be eligible under the scheme and whether grandfathering of existing offsets will be permissible.11 Any restriction concerning the type or vintage of eligible offsets may increase the cost of compliance and thus create an economic burden for many Operators under CORSIA. The expected bottom-line impact of CORSIA compliance for airlines has caught the attention of international credit rating agencies such as Moody’s, who suggested in a recent report that

“[g]rowing carbon offset costs have the potential to become significant relative to operating profit…carbon costs have the potential to lower operating income by between 4% and 15% by 2025, and by between 7% and 35% by 2030, all else being equal.”12

CORSIA compliance will present aircraft owners with several commercial and legal risks and challenges. One such challenge is identifying who will be responsible for compliance under the scheme where the operator of a flight has not been identified. The first line of inquiry is the ICAO designator,13 followed by the aircraft registration mark and holder of an Aircraft Operator Certificate (AOC). If the ICAO designator and AOC holder cannot be readily established, CORSIA compliance will then will fall to the aircraft owner identified in the aircraft registration documentation.14 Should an Operator fail to submit an emissions monitoring plan and annual emissions reports, its CORSIA Contracting State may not be able to identify the operator of an aircraft’s international flight activity or, consequently, the responsibility for its emissions from such activity, and therefore CORSIA compliance obligations would automatically be attributed to the aircraft owner. Any such risk may become compounded for aircraft lessors and investors in asset-backed finance portfolio transactions.

The fact that ICAO has no legal rights to enforce the CORSIA SARPs creates risk that local governments and regulators may hold an aircraft owner responsible for CORSIA non-compliance. Each individual Contracting State is responsible for transcribing CORSIA into its domestic law. While it remains unclear as to exactly how (if at all) and when each Contracting State will do so, the possibility certainly exists for states to pass laws allowing relevant government entities to impose a lien on, and seize and potentially sell, an aircraft pending cancellation of sufficient emissions offsets for the operator’s entire fleet—similar to the Eurocontrol fleet lien and applicable regulations in certain jurisdictions under the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS)—notwithstanding the rights of the aircraft owner or mortgagee.15 In addition, legal and financial consequences may arise should an Operator fail to cancel a sufficient quantity of eligible emissions offset units to cover its existing obligations following an insolvency declaration.

Furthermore, current lease and loan documentation practices need to be reconsidered in light of the differences between compliance under EU ETS and compliance under CORSIA. EU ETS runs on an annual reporting and emissions allowance surrender cycle. In contrast, while CORSIA will have an annual emissions reporting cycle, cancellation of emissions unit offsets will, starting in 2020,16 be subject to a three-year compliance cycle. This longer cycle is likely to cause aircraft owners to accumulate a much greater credit risk exposure. Requiring an Operator, as a condition precedent under a lease or loan agreement, to deliver a CORSIA “Letter of Authority” permitting the relevant regulator to disclose the Operator’s emissions obligations as a means for a lessor or mortgagee to monitor this credit exposure will likely have little if any effect. It is presently unknown to what extent, if any, Contracting State regulators will honor such letters of authority, as CORSIA allows aircraft Operators to request regulators to keep commercially sensitive emissions data confidential.17 Moreover, until the end of the three-year compliance cycle expires, the CORSIA regulator will not be able to confirm the level of an Operator’s compliance and financial liability, by which point the damage (and potential exposure for the lessor or mortgagee) may be irreversible. Also, the price of eligible emissions units under CORSIA (measuring the cost of compliance) will not be known until the time of purchase by the Operator, unless an Operator hedges its CORSIA exposure through a forward contract with a carbon broker.

Should the EU decide to transcribe CORSIA18 as an annex to EU ETS, then the existing enforcement measures for non-compliance, being a statutory penalty of €100 per ton of CO219 plus additional local fees, penalties and the rights of aircraft seizure, detention and sale may apply. Meanwhile, the UK is scheduled to exit the EU ETS in March 201920 and is currently considering its options, including whether to seek to negotiate with the EU to opt back into EU ETS, or alternatively set up its own ETS or UK aviation carbon offset scheme for domestic and intra-European Economic Area (EEA) flights. The UK remains fully committed to CORSIA for international flights outside the EEA. Meanwhile, the uncertainties surrounding CORSIA could create challenges in disclosing climate change-related risks, trends or factors in publicly listed leasing and finance company annual financial reports21 and offering memoranda for securitization transactions that require a credit rating.22

In sum, given the plethora of potential risks and uncertainties under CORSIA, it is important that aircraft owners and financiers understand the basic functions of the scheme, keep an eye on the evolving landscape of requirements and consequences of non-compliance, and consider implementation of risk mitigation measures in lease and loan documentation. While there is considerable momentum for commencing and implementing CORSIA as a global method for reducing aviation emissions, the scheme still presents many unknowns and risks, but few clear solutions.

Vedder Price can advise on developing CORSIA-related provisions in aircraft lease and loan agreements. Avocet Risk Management is positioned to provide CORSIA risk management and mitigation solutions to aircraft owners and financiers.

- 1See https://www.icao.int/Newsroom/Pages/Historic-agreement-reached-to-mitigate-international-aviation-emissions.aspx.

- 2 See https://www.unitingaviation.com/publications/Annex-16-Vol-04/#page=1.

- 3 ICAO’s CORSIA uses the term “Aeroplane Operator.”

- 4 Operators subject to CORSIA’s technical exemptions being those (i) with annual emissions of less than 10,000 t/CO2, (ii) operating humanitarian medical and firefighting flights, (iii) operating military and State flights (Presidential, customs, police etc.), and (iv) operating helicopters.

- 5 10,000 metric tons of CO2 is approximately equivalent to 4,000,000 liters (1,000,000 US gallons) of JET-A aviation fuel. Source UK Department of Transport.

- 6 The terms “Contracting State” and “Member State” are used interchangeably by ICAO.

- 7 An “Emissions Monitoring Plan” is a collaborative tool between the state and the aircraft operator that identifies the most appropriate means and methods for CO2 emissions monitoring on an operator-specific basis, and facilitates the reporting of required information to the state.

- 8 The first edition of ICAO’s SARPs (Annex 16, Volume IV), was adopted on June 27, 2018. Such parts of the SARPs that are not disapproved by more than half of the total number of Contracting States on or before October 22, 2018 became effective on that date and will become applicable on January 1, 2019.

- 9 http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14330-2018-ADD-1/en/pdf.

- 10 CORSIA uses the term “Aeroplane Owner” as the scheme is only applicable to fixed wing aircraft and excludes rotor wing aircraft.

- 11 Particularly Carbon Reduction Emissions offset units created under the United Nations’ Clean Development Mechanism See Moody's “Passenger Airlines—Global: Pricing power, route mix to determine credit implications of carbon transition” (April 2018). https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-Carbon-transition-risk-varies-by-airline-with-international-carriers--PR_382486?WT.mc_id=AM%7eRmluYW56ZW4ubmV0X1JTQl9SYXRpbmdzX05ld3NfTm9fVHJhbnNsYXRpb25z%7e20180418_PR_382486.

- 12 Being the three (3) letter call sign, should the aircraft operator have such a call sign. See clause 1.1.3 of the CORSIA SARPs, https://www.unitingaviation.com/publications/Annex-16-Vol-04/#page=1

- 13 See clause 1.1.4 of the CORSIA SARPs, https://www.unitingaviation.com/publications/Annex-16-Vol-04/#page=1.

- 14 For example, under the UK’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Regulations, the UK Civil Aviation Authority has the right of seizure, detention and sale of aircraft in the event of persistent EU ETS aviation non-compliance. However, liens are not applicable where an aircraft is owned by a lessor and liens are not transferable to a new operator of an aircraft subject to penalties (i.e., “follow the metal”).

- 15 The first CORSIA emissions credits are scheduled to be cancelled on January 31, 2025.

- 16 ICAO’s SARPs (Annex 16, Volume IV) Chapter 2.3.16/2.3.17.

- 17 Depending on whether the EU considers that CORSIA meets the terms of Bratislava Declaration.

- 18 EU Directive 2008/101/EC, includes provision of an excess emissions penalty of EUR 100 applies for each ton of carbon dioxide equivalent emitted for which the aircraft operator has not surrendered allowances. Payment of the excess emissions penalty does not release the operator or aircraft operator from the obligation to surrender an amount of allowances equal to those excess emissions when surrendering allowances in relation to the following calendar year. Potentially a similar penalty regime may also apply for CORSIA.

- 19 But will require aircraft operators reporting to the UK regulator to continue to comply with EU ETS for the 2019 emissions compliance year.

- 20 At least 40 countries, including all EU Member States currently have mandatory emissions reporting programs in place, World Resources Institute, https://www.wri.org/blog/2015/05/global-look-mandatory-greenhouse-gas-reporting-programs.

- 21 Credit risk arising from CORSIA should be a factor in future rating agency modelling.

Professionals

-

Services