PDP Financing: An Overview

This article discusses pre-delivery payment—or PDP—financing transactions for aircraft. PDPs are progress payments that a purchaser makes to a manufacturer while new aircraft are being built.

The Basic Structure

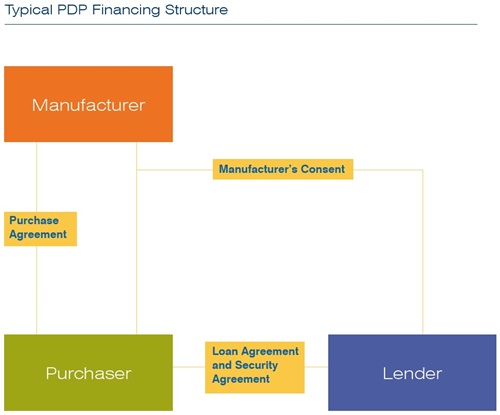

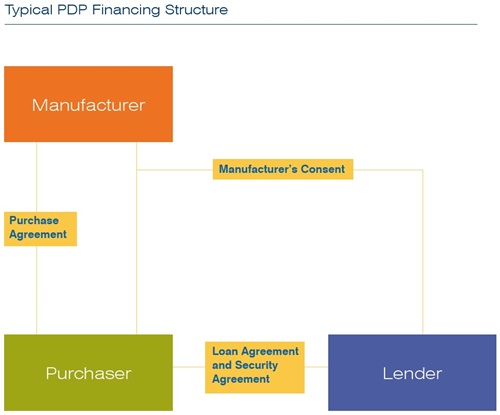

In a normal PDP financing the lender finances PDPs by advancing a secured loan. Interest is payable throughout the term of the loan and principal is repayable upon delivery of each aircraft securing the loan. The purchaser grants a lien in favor of the lender over its rights in an aircraft purchase agreement. The purchaser also arranges a tripartite agreement with the manufacturer (called a manufacturer’s consent or step-in agreement). This includes the manufacturer’s acknowledgment of the lender’s lien and agreements as to the parties’ rights to the aircraft and the PDPs following a default by the purchaser. A structure diagram for a traditional PDP financing is as follows:

The manufacturer’s consent sets forth the price at which the lender can purchase an aircraft if the lender steps in following a purchaser default. The purchase price may be impacted by changes to the aircraft that occur during production, escalation of the purchase price or other factors. Such purchase price adjustments are usually addressed by requiring prepayment of the loan or the posting of cash collateral in the amount of the increased cost.

The lender values its collateral based on the purchase price for the aircraft set forth in the manufacturer’s consent, less the amount of “equity” PDPs that have been paid by the purchaser directly. Equity PDPs are not funded by the lender and are applied to reduce the total of the purchase price payable by the lender upon enforcement.

The manufacturer’s consent will also contain the manufacturer’s agreements not to set off or reapply PDPs and/or an agreement that if it does set off or reapply PDPs it will give the lender a credit for the difference.

Enforcement Mechanics

Manufacturer’s consents provide that following either termination of the purchase agreement or an event of default by the purchaser, the lender has the right, but not the obligation, to elect to step in and replace its borrower as purchaser of the aircraft. The consequence of not making this election is often that the lender loses its rights to its already-funded PDPs and its rights in the collateral.

This presents the lender with a difficult choice upon enforcement. It must either step in and be responsible for all of the obligations of the purchaser under the purchase agreement—including an obligation to pay an amount to take delivery of the aircraft that is many times the amount of the PDPs funded by the lender—or walk away from all or a significant portion of its collateral.

If the lender steps in, it will want to be able to dispose of its collateral as soon as possible, by assigning its right to purchase the aircraft before delivery. The lender will not want to wait for the aircraft to be delivered before disposing of its collateral, which may not be for a number of years. Manufacturer’s consents often restrict the assignment right, but should allow assignment subject to consent (not to be unreasonably withheld).

Manufacturer’s consents also give the manufacturer a “purchase option”, giving the manufacturer the right, but not the obligation, to buy out the lender’s loan during a relatively short window of time following the lender exercising its purchase right. The buy-out is usually exercisable for the full amount of principal, plus a negotiated amount of interest and other amounts.

Bankruptcy Issues

Bankruptcy issues are of particular importance in PDP financing. Lenders must rely on general bankruptcy principles dealing with executory contracts, and do not have the benefit of an equivalent of Section 1110 of the Bankruptcy Code, which requires that an air-carrier debtor keep current on its obligations under an aircraft financing or lose the protection of the automatic stay 60 days after the commencement of a Chapter 11 bankruptcy case.

In addition, “claw-back” risk is a concern for both lenders and manufacturers. This arises in the context of a purchaser bankruptcy, where the debtor or administrator of the purchaser’s bankrupt estate claims that the manufacturer must repay the PDPs made by the purchaser, leaving either the lender to pay the PDPs to the manufacturer a second time, or requiring the manufacturer to deliver an aircraft for which it has not been fully paid.

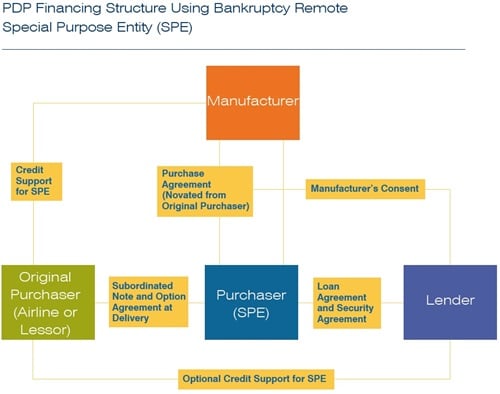

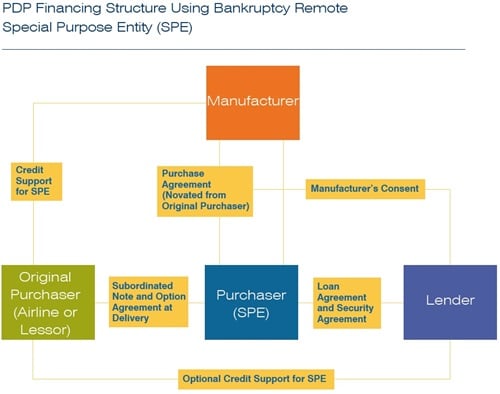

Some manufacturers and lenders have been more likely to accept claw-back risk if a “bankruptcy-remote” structure is used. In such a structure the purchase agreement is transferred to a special purpose entity, with the intention that the special purpose entity will be shielded from a bankruptcy of the original purchaser. The idea of using such a structure is to reduce the likelihood of the purchaser becoming bankrupt to such an extent that the allocation of claw-back risk becomes theoretical. A diagram of a typical bankruptcy-remote PDP structure is as follows:

Bankruptcy remoteness is more tenable in jurisdictions where courts look solely to formal, documented separateness of the original purchaser and the special purpose entity in considering whether they should be consolidated. Because of this, market practice is to utilize special purpose entities in non-United States jurisdictions with insolvency laws that do not apply United States law “true sale” and “substantive consolidation” concepts, and where the economic substance of the transaction does not play into the separateness analysis. This is particularly the case for transactions where the original purchaser also has no United States nexus.

In light of the possible consolidation risk affecting “bankruptcy remote” PDP structures in some jurisdictions, parties also occasionally resort to alternative financing structures to mitigate the parties’ insolvency risks. Some transactions have been implemented that reduce claw-back risk even more than bankruptcy remote structures.

More Information?

The article above is a summary of a more detailed piece that has been published in the Spring 2018 edition of The Journal of Structured Finance, which is available at http://jsf.iijournals.com/content/early/2018/04/17/jsf.2018.1.064 (subscription may be required).

Click below to download the complete newsletter featuring this article.

Vedder Thinking | Articles PDP Financing: An Overview

Newsletter

August 2018

This article discusses pre-delivery payment—or PDP—financing transactions for aircraft. PDPs are progress payments that a purchaser makes to a manufacturer while new aircraft are being built.

The Basic Structure

In a normal PDP financing the lender finances PDPs by advancing a secured loan. Interest is payable throughout the term of the loan and principal is repayable upon delivery of each aircraft securing the loan. The purchaser grants a lien in favor of the lender over its rights in an aircraft purchase agreement. The purchaser also arranges a tripartite agreement with the manufacturer (called a manufacturer’s consent or step-in agreement). This includes the manufacturer’s acknowledgment of the lender’s lien and agreements as to the parties’ rights to the aircraft and the PDPs following a default by the purchaser. A structure diagram for a traditional PDP financing is as follows:

The manufacturer’s consent sets forth the price at which the lender can purchase an aircraft if the lender steps in following a purchaser default. The purchase price may be impacted by changes to the aircraft that occur during production, escalation of the purchase price or other factors. Such purchase price adjustments are usually addressed by requiring prepayment of the loan or the posting of cash collateral in the amount of the increased cost.

The lender values its collateral based on the purchase price for the aircraft set forth in the manufacturer’s consent, less the amount of “equity” PDPs that have been paid by the purchaser directly. Equity PDPs are not funded by the lender and are applied to reduce the total of the purchase price payable by the lender upon enforcement.

The manufacturer’s consent will also contain the manufacturer’s agreements not to set off or reapply PDPs and/or an agreement that if it does set off or reapply PDPs it will give the lender a credit for the difference.

Enforcement Mechanics

Manufacturer’s consents provide that following either termination of the purchase agreement or an event of default by the purchaser, the lender has the right, but not the obligation, to elect to step in and replace its borrower as purchaser of the aircraft. The consequence of not making this election is often that the lender loses its rights to its already-funded PDPs and its rights in the collateral.

This presents the lender with a difficult choice upon enforcement. It must either step in and be responsible for all of the obligations of the purchaser under the purchase agreement—including an obligation to pay an amount to take delivery of the aircraft that is many times the amount of the PDPs funded by the lender—or walk away from all or a significant portion of its collateral.

If the lender steps in, it will want to be able to dispose of its collateral as soon as possible, by assigning its right to purchase the aircraft before delivery. The lender will not want to wait for the aircraft to be delivered before disposing of its collateral, which may not be for a number of years. Manufacturer’s consents often restrict the assignment right, but should allow assignment subject to consent (not to be unreasonably withheld).

Manufacturer’s consents also give the manufacturer a “purchase option”, giving the manufacturer the right, but not the obligation, to buy out the lender’s loan during a relatively short window of time following the lender exercising its purchase right. The buy-out is usually exercisable for the full amount of principal, plus a negotiated amount of interest and other amounts.

Bankruptcy Issues

Bankruptcy issues are of particular importance in PDP financing. Lenders must rely on general bankruptcy principles dealing with executory contracts, and do not have the benefit of an equivalent of Section 1110 of the Bankruptcy Code, which requires that an air-carrier debtor keep current on its obligations under an aircraft financing or lose the protection of the automatic stay 60 days after the commencement of a Chapter 11 bankruptcy case.

In addition, “claw-back” risk is a concern for both lenders and manufacturers. This arises in the context of a purchaser bankruptcy, where the debtor or administrator of the purchaser’s bankrupt estate claims that the manufacturer must repay the PDPs made by the purchaser, leaving either the lender to pay the PDPs to the manufacturer a second time, or requiring the manufacturer to deliver an aircraft for which it has not been fully paid.

Some manufacturers and lenders have been more likely to accept claw-back risk if a “bankruptcy-remote” structure is used. In such a structure the purchase agreement is transferred to a special purpose entity, with the intention that the special purpose entity will be shielded from a bankruptcy of the original purchaser. The idea of using such a structure is to reduce the likelihood of the purchaser becoming bankrupt to such an extent that the allocation of claw-back risk becomes theoretical. A diagram of a typical bankruptcy-remote PDP structure is as follows:

Bankruptcy remoteness is more tenable in jurisdictions where courts look solely to formal, documented separateness of the original purchaser and the special purpose entity in considering whether they should be consolidated. Because of this, market practice is to utilize special purpose entities in non-United States jurisdictions with insolvency laws that do not apply United States law “true sale” and “substantive consolidation” concepts, and where the economic substance of the transaction does not play into the separateness analysis. This is particularly the case for transactions where the original purchaser also has no United States nexus.

In light of the possible consolidation risk affecting “bankruptcy remote” PDP structures in some jurisdictions, parties also occasionally resort to alternative financing structures to mitigate the parties’ insolvency risks. Some transactions have been implemented that reduce claw-back risk even more than bankruptcy remote structures.

More Information?

The article above is a summary of a more detailed piece that has been published in the Spring 2018 edition of The Journal of Structured Finance, which is available at http://jsf.iijournals.com/content/early/2018/04/17/jsf.2018.1.064 (subscription may be required).

Click below to download the complete newsletter featuring this article.

Professionals

-

Services