DOJ Declinations under FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy

The Department of Justice’s (“DOJ”) policy regarding corporate enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) has evolved in meaningful ways since 2016. While the policy developments themselves have been frequently discussed, publicly available declination letters from 2018 through the present provide valuable, concrete examples of how the policy is actually being implemented. This article provides an examination of the facts surrounding declinations under the current policy and highlights key trends and takeaways from the DOJ’s six most recent declination letters.

DOJ’s FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy

In April 2016, Assistant Attorney General Leslie R. Caldwell announced the DOJ’s FCPA Pilot Program (the “Pilot Program”). The Pilot Program was to run for one year and was “designed to motivate companies to voluntarily self-disclose FCPA-related misconduct, fully cooperate with the Fraud Section, and, where appropriate, remediate flaws in their controls and compliance programs.”1 The source of that motivation was greater clarity from the DOJ on its expectations for companies seeking cooperation credit, and greater clarity on the potential outcomes for cooperating companies. In short, companies that voluntarily self-disclosed an FCPA-related violation, properly remediated and fully cooperated with the DOJ would be eligible for consideration for a declination of prosecution and, short of that, would be eligible for a “reduction of up to 50 percent below the low end of the applicable U.S. Sentencing Guidelines fine range” and avoidance of appointment of a monitor.2 Companies that did not voluntarily self-disclose the FCPA violation but later cooperated and remediated would still be eligible for “markedly less” cooperation credit.3

In March 2017, the DOJ announced that the Pilot Program would be extended. Then, on November 29, 2017, then-Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein announced the DOJ’s “revised FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy” (the “Revised Policy”), now incorporated into the Justice Manual ("JM").4 The goal of the Revised Policy was to “provide transparency about the benefits available if [companies] satisfy the requirements [and to help] corporate officers and board members to better understand the costs and benefits of cooperation.”5 To that end, the Revised Policy “specifies what [the DOJ] mean[s] by voluntary disclosure, full cooperation, and timely and appropriate remediation.”

Rosenstein highlighted three key aspects of the Revised Policy, namely, (1) companies that voluntarily self-disclose, fully cooperate, and timely and appropriately remediate are presumed to receive a declination, and such a presumption can be overcome only by aggravating circumstances regarding the nature and seriousness of the offense or recidivist status; (2) companies that satisfy all requirements for a declination but cannot receive a declination due to aggravating circumstances (except for recidivism) will receive a recommendation of a 50 percent reduction from the low end of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines; and (3) the Revised Policy provides greater clarity about how the DOJ evaluates the appropriateness of compliance programs, which “vary depending on the size and resources of a business.”6

The Revised Policy spells out in significant detail what the DOJ expects in the form of voluntary self-disclosure, full cooperation, and timely and appropriate remediation.7 At a high level, the standards set forth in the Revised Policy include the following:

- Voluntary Self-Disclosure: must occur “prior to an imminent threat of disclosure or government investigation”; must be disclosed “within a reasonably prompt time after becoming aware of the offense”; and must involve disclosure of “all relevant facts . . . including as to any individuals substantially involved in or responsible for the misconduct at issue”

- Full Cooperation: timely disclosure of all relevant facts (including attribution to specific sources, updates on internal investigation, and all facts relating to potential criminal conduct by company insiders or outsiders); proactive cooperation even when not specifically requested by the DOJ; timely preservation, collection, and disclosure of relevant documents (including foreign-language translation, facilitation of third-party productions, and assistance with obtaining overseas documents); de-confliction of witness interviews; presenting key witnesses for interviews by the DOJ

- Timely and Appropriate Remediation: thorough analysis of root cause and remediation designed to address root cause; implementation of effective compliance/ethics program; discipline of responsible employees; retention of business records; disgorgement and “any additional steps that demonstrate recognition of the seriousness of the company’s misconduct”

Through a series of announcements and formal modifications in 2018 and 2019, the DOJ has continued to fine-tune the Revised Policy. This has included—for example—clarifying that the Revised Policy applies to FCPA violations that are uncovered in the context of corporate mergers or acquisitions; providing additional guidance on de-confliction; requiring implementation of “appropriate guidance and controls on the use of personal communications and ephemeral messaging platforms that undermine the company’s ability to appropriately retain business records or communications”8; modifying the scope of individuals about whom “all relevant facts” must be disclosed; and clarifying that “a company may not be in a position to know all relevant facts at the time of a voluntary self-disclosure [and that] [i]n such circumstances, a company should make clear that it is making its disclosure based upon a preliminary investigation or assessment of information.”9

Declinations from 2018 to the Present

As 2018 was the first full year under the Revised Policy, it provides a good starting point for an examination of how the DOJ evaluates companies under the Revised Policy. This evaluation is aided by the fact that the DOJ publishes its FCPA declination letters.10 There have been six published corporate declinations in FCPA investigations since the start of 2018:

In re: Dun & Bradstreet Corporation (“D&B”): Two of D&B’s Chinese subsidiaries used third-party agents to make improper payments to obtain valuable data for use by D&B in its business of providing financial information.

In re: Guralp Systems Limited (“Guralp”): Guralp made improper payments to Korean government officials in exchange for business advantages, including confidential bidding process information and recommendations that a government agency purchase equipment from Guralp.

In re: Insurance Corporation of Barbados Limited (“ICBL”): ICBL made improper payments to a Barbadian government official to procure insurance contracts.

In re: Polycom Inc. (“Polycom”): Polycom’s Chinese subsidiary used third-party agents to make improper payments to Chinese government officials to procure assistance in securing deals for Polycom products.

In re: Cognizant Technology Solutions Corporation (“Cognizant”): Cognizant authorized a construction firm building its campus in India to bribe a senior government official.

In re: Quad/Graphics Inc. (“Quad/Graphics”): Quad/Graphics’ Peruvian subsidiary made payments to third-party intermediaries that were used to bribe Peruvian government officials in an effort to obtain government contracts and to minimize tax liabilities and performance-related penalties under the government contracts.

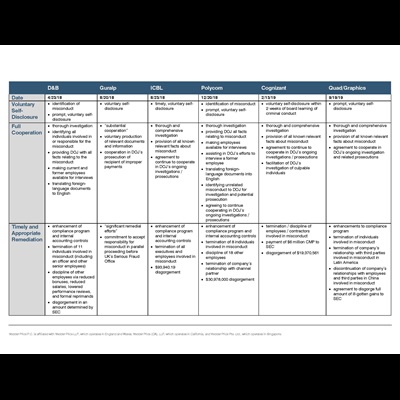

The following chart breaks down the declination letters issued in each of these investigations, noting where possible the specific language used by the DOJ to describe each company’s compliance with the Revised Policy’s requirements of voluntary self-disclosure, full cooperation, and timely and appropriate remediation.

Click here to view the chart.

Key Takeaways

The data contained in the declination letters, as summarized in the foregoing chart, provides valuable insight into what specifically is required of a company seeking a declination in an FCPA investigation (or what is required for a company being investigated by the DOJ for non-FCPA criminal conduct to present a compelling case that the Revised Policy, as non-binding guidance, warrants a declination). These insights include:

Robust compliance programs matter. Companies will not be eligible for a declination if they do not self-report the FCPA violation. And a company cannot self-report what it does not know. While compliance functions should be reasonably tailored to the size and needs of a given company (i.e., no “one size fits all” approach), it is imperative that the compliance function detect (via internal accounting controls, internal whistleblower complaints, etc.) the wrongdoing in order to have a chance for a declination.

The stakes of hoping the DOJ does not find out about past misconduct are higher. Now that the DOJ has committed to issuing declinations (absent recidivism or aggravating circumstances) when certain standards are met, there is less of a reason for companies to quietly sit on evidence of FCPA violations and hope the DOJ doesn’t find out. Hoping that the misconduct goes unnoticed is a more reasonable risk when the consequences of self-disclosure may be comparable in severity to the consequences of the DOJ uncovering the misconduct first. That is no longer the reality of FCPA enforcement.

Monetary scope of misconduct does not appear to be a factor in issuing declinations. The 2018 and 2019 declinations run the gamut in terms of disgorgement, ranging from less than $100,000 to greater than $30 million. In other words, companies that obtain large profits from their violative conduct appear no less likely to receive a declination than companies obtaining more modest profits, so long as the DOJ’s requirements for a declination are met.

Strong emphasis on individual culpability. The declinations highlighted above show a consistent theme: identification and punishment of culpable individuals. Five of the six declinations highlighted above specifically referenced the company’s termination and/or discipline of culpable individuals; two of the six specifically referenced termination of senior/executive personnel; and two of the six specifically referenced cooperation in the DOJ’s investigation/prosecution of culpable individuals (above and beyond the standard language about cooperating with general ongoing investigations and prosecutions). The DOJ’s emphasis on individual culpability is apparently sufficiently strong that companies with senior/executive-level involvement in misconduct—considered an aggravating factor weighing against the issuance of a declination—were still able to receive a declination based on their cooperation, including internal discipline of the culpable individuals and cooperation with the DOJ’s ongoing investigations and prosecutions.

Keeping good company is important. Four of the above-referenced matters involved improper payments by third-party agents of a company. In three of those matters, the declination letter specifically referenced termination of the third-party relationships as part of the company’s full remediation.

Strong employment policies and practices can help pave the way for a declination. Employment policies and practices can strengthen a company’s ability to present key witnesses for DOJ interviews as part of its cooperation. The declination letters in two of the above-referenced cases specifically noted the presentment of employees for interviews by the DOJ, and one specifically credited a company for producing former employees for DOJ interviews. The ability of a company to provide its current and/or former employees for interviews with federal authorities may be directly related to the terms of employment agreements, employee handbooks, separation agreements, etc. Similarly, in light of the emphasis on punishment of culpable individuals as part of full remediation, it is important that employment policies and procedures offer a company the discretion to implement disciplinary and/or termination measures as necessary.

Promptness matters. The Revised Policy set forth in the JM requires self-disclosure to the DOJ “within a reasonably prompt time after becoming aware of the offense.”11 It further notes that “the burden [is] on the company to demonstrate timeliness.” While many of the above-refenced declination letters cited vaguely to the company’s “prompt” or “timely” self-disclosure, one letter specifically noted that the disclosure occurred within two weeks of the company’s board becoming aware of the misconduct. While this two-week turnaround is an example and not a rule, it sets an exacting standard for companies attempting to shoulder the burden of proving that self-disclosure to the DOJ was reasonably prompt.

Thorough investigations are paramount to success under the Revised Policy. Five of the six above-referenced declination letters specifically touted the thoroughness of the company’s investigation into the misconduct, and it is axiomatic that a thorough investigation is necessary to allow a company to satisfy the exacting qualifications for a declination. A sufficiently robust investigation requires a company to commit immediately to fully uncovering the truth, remediating any problems that are uncovered, and dedicating the resources necessary to do so. This may entail engaging the services of multiple law firms (audit committee counsel, company counsel, counsel for certain key individuals), a forensic accounting firm, a company specializing in foreign-language translation, interpreters for witness interviews of non-English-speaking personnel, forensic vendors to collect electronic documents and data, a compliance consultant, etc. Even if a company ultimately decides against self-disclosure, a commitment to the type of comprehensive investigation that will satisfy the standards of the Revised Policy is necessary from the outset in order to afford corporate decision makers maximum optionality when deciding how to handle the misconduct.

For additional information, please contact Ryan S. Hedges at +1 (312) 609 7728, Junaid A. Zubairi at +1 (312) 609 7720, Anthony Pacheco at +1 (424) 204 7773 or Joshua Nichols at +1 (312) 609 7724 or another Vedder Price attorney with whom you have worked.

1 https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/blog/criminal-division-launches-new-fcpa-pilot-program

2 Id.

3 Id.

4 https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-rosenstein-delivers-remarks-34th-international-conference-foreign

5 Id.

6 Id.

7 https://www.justice.gov/jm/jm-9-47000-foreign-corrupt-practices-act-1977#9-47.120

8 Id.

9 Id.

10 https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/corporate-enforcement-policy/declinations

11 https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/corporate-enforcement-policy

Vedder Thinking | Articles DOJ Declinations under FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy

Article

May 4, 2020

The Department of Justice’s (“DOJ”) policy regarding corporate enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) has evolved in meaningful ways since 2016. While the policy developments themselves have been frequently discussed, publicly available declination letters from 2018 through the present provide valuable, concrete examples of how the policy is actually being implemented. This article provides an examination of the facts surrounding declinations under the current policy and highlights key trends and takeaways from the DOJ’s six most recent declination letters.

DOJ’s FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy

In April 2016, Assistant Attorney General Leslie R. Caldwell announced the DOJ’s FCPA Pilot Program (the “Pilot Program”). The Pilot Program was to run for one year and was “designed to motivate companies to voluntarily self-disclose FCPA-related misconduct, fully cooperate with the Fraud Section, and, where appropriate, remediate flaws in their controls and compliance programs.”1 The source of that motivation was greater clarity from the DOJ on its expectations for companies seeking cooperation credit, and greater clarity on the potential outcomes for cooperating companies. In short, companies that voluntarily self-disclosed an FCPA-related violation, properly remediated and fully cooperated with the DOJ would be eligible for consideration for a declination of prosecution and, short of that, would be eligible for a “reduction of up to 50 percent below the low end of the applicable U.S. Sentencing Guidelines fine range” and avoidance of appointment of a monitor.2 Companies that did not voluntarily self-disclose the FCPA violation but later cooperated and remediated would still be eligible for “markedly less” cooperation credit.3

In March 2017, the DOJ announced that the Pilot Program would be extended. Then, on November 29, 2017, then-Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein announced the DOJ’s “revised FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy” (the “Revised Policy”), now incorporated into the Justice Manual ("JM").4 The goal of the Revised Policy was to “provide transparency about the benefits available if [companies] satisfy the requirements [and to help] corporate officers and board members to better understand the costs and benefits of cooperation.”5 To that end, the Revised Policy “specifies what [the DOJ] mean[s] by voluntary disclosure, full cooperation, and timely and appropriate remediation.”

Rosenstein highlighted three key aspects of the Revised Policy, namely, (1) companies that voluntarily self-disclose, fully cooperate, and timely and appropriately remediate are presumed to receive a declination, and such a presumption can be overcome only by aggravating circumstances regarding the nature and seriousness of the offense or recidivist status; (2) companies that satisfy all requirements for a declination but cannot receive a declination due to aggravating circumstances (except for recidivism) will receive a recommendation of a 50 percent reduction from the low end of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines; and (3) the Revised Policy provides greater clarity about how the DOJ evaluates the appropriateness of compliance programs, which “vary depending on the size and resources of a business.”6

The Revised Policy spells out in significant detail what the DOJ expects in the form of voluntary self-disclosure, full cooperation, and timely and appropriate remediation.7 At a high level, the standards set forth in the Revised Policy include the following:

- Voluntary Self-Disclosure: must occur “prior to an imminent threat of disclosure or government investigation”; must be disclosed “within a reasonably prompt time after becoming aware of the offense”; and must involve disclosure of “all relevant facts . . . including as to any individuals substantially involved in or responsible for the misconduct at issue”

- Full Cooperation: timely disclosure of all relevant facts (including attribution to specific sources, updates on internal investigation, and all facts relating to potential criminal conduct by company insiders or outsiders); proactive cooperation even when not specifically requested by the DOJ; timely preservation, collection, and disclosure of relevant documents (including foreign-language translation, facilitation of third-party productions, and assistance with obtaining overseas documents); de-confliction of witness interviews; presenting key witnesses for interviews by the DOJ

- Timely and Appropriate Remediation: thorough analysis of root cause and remediation designed to address root cause; implementation of effective compliance/ethics program; discipline of responsible employees; retention of business records; disgorgement and “any additional steps that demonstrate recognition of the seriousness of the company’s misconduct”

Through a series of announcements and formal modifications in 2018 and 2019, the DOJ has continued to fine-tune the Revised Policy. This has included—for example—clarifying that the Revised Policy applies to FCPA violations that are uncovered in the context of corporate mergers or acquisitions; providing additional guidance on de-confliction; requiring implementation of “appropriate guidance and controls on the use of personal communications and ephemeral messaging platforms that undermine the company’s ability to appropriately retain business records or communications”8; modifying the scope of individuals about whom “all relevant facts” must be disclosed; and clarifying that “a company may not be in a position to know all relevant facts at the time of a voluntary self-disclosure [and that] [i]n such circumstances, a company should make clear that it is making its disclosure based upon a preliminary investigation or assessment of information.”9

Declinations from 2018 to the Present

As 2018 was the first full year under the Revised Policy, it provides a good starting point for an examination of how the DOJ evaluates companies under the Revised Policy. This evaluation is aided by the fact that the DOJ publishes its FCPA declination letters.10 There have been six published corporate declinations in FCPA investigations since the start of 2018:

In re: Dun & Bradstreet Corporation (“D&B”): Two of D&B’s Chinese subsidiaries used third-party agents to make improper payments to obtain valuable data for use by D&B in its business of providing financial information.

In re: Guralp Systems Limited (“Guralp”): Guralp made improper payments to Korean government officials in exchange for business advantages, including confidential bidding process information and recommendations that a government agency purchase equipment from Guralp.

In re: Insurance Corporation of Barbados Limited (“ICBL”): ICBL made improper payments to a Barbadian government official to procure insurance contracts.

In re: Polycom Inc. (“Polycom”): Polycom’s Chinese subsidiary used third-party agents to make improper payments to Chinese government officials to procure assistance in securing deals for Polycom products.

In re: Cognizant Technology Solutions Corporation (“Cognizant”): Cognizant authorized a construction firm building its campus in India to bribe a senior government official.

In re: Quad/Graphics Inc. (“Quad/Graphics”): Quad/Graphics’ Peruvian subsidiary made payments to third-party intermediaries that were used to bribe Peruvian government officials in an effort to obtain government contracts and to minimize tax liabilities and performance-related penalties under the government contracts.

The following chart breaks down the declination letters issued in each of these investigations, noting where possible the specific language used by the DOJ to describe each company’s compliance with the Revised Policy’s requirements of voluntary self-disclosure, full cooperation, and timely and appropriate remediation.

Click here to view the chart.

Key Takeaways

The data contained in the declination letters, as summarized in the foregoing chart, provides valuable insight into what specifically is required of a company seeking a declination in an FCPA investigation (or what is required for a company being investigated by the DOJ for non-FCPA criminal conduct to present a compelling case that the Revised Policy, as non-binding guidance, warrants a declination). These insights include:

Robust compliance programs matter. Companies will not be eligible for a declination if they do not self-report the FCPA violation. And a company cannot self-report what it does not know. While compliance functions should be reasonably tailored to the size and needs of a given company (i.e., no “one size fits all” approach), it is imperative that the compliance function detect (via internal accounting controls, internal whistleblower complaints, etc.) the wrongdoing in order to have a chance for a declination.

The stakes of hoping the DOJ does not find out about past misconduct are higher. Now that the DOJ has committed to issuing declinations (absent recidivism or aggravating circumstances) when certain standards are met, there is less of a reason for companies to quietly sit on evidence of FCPA violations and hope the DOJ doesn’t find out. Hoping that the misconduct goes unnoticed is a more reasonable risk when the consequences of self-disclosure may be comparable in severity to the consequences of the DOJ uncovering the misconduct first. That is no longer the reality of FCPA enforcement.

Monetary scope of misconduct does not appear to be a factor in issuing declinations. The 2018 and 2019 declinations run the gamut in terms of disgorgement, ranging from less than $100,000 to greater than $30 million. In other words, companies that obtain large profits from their violative conduct appear no less likely to receive a declination than companies obtaining more modest profits, so long as the DOJ’s requirements for a declination are met.

Strong emphasis on individual culpability. The declinations highlighted above show a consistent theme: identification and punishment of culpable individuals. Five of the six declinations highlighted above specifically referenced the company’s termination and/or discipline of culpable individuals; two of the six specifically referenced termination of senior/executive personnel; and two of the six specifically referenced cooperation in the DOJ’s investigation/prosecution of culpable individuals (above and beyond the standard language about cooperating with general ongoing investigations and prosecutions). The DOJ’s emphasis on individual culpability is apparently sufficiently strong that companies with senior/executive-level involvement in misconduct—considered an aggravating factor weighing against the issuance of a declination—were still able to receive a declination based on their cooperation, including internal discipline of the culpable individuals and cooperation with the DOJ’s ongoing investigations and prosecutions.

Keeping good company is important. Four of the above-referenced matters involved improper payments by third-party agents of a company. In three of those matters, the declination letter specifically referenced termination of the third-party relationships as part of the company’s full remediation.

Strong employment policies and practices can help pave the way for a declination. Employment policies and practices can strengthen a company’s ability to present key witnesses for DOJ interviews as part of its cooperation. The declination letters in two of the above-referenced cases specifically noted the presentment of employees for interviews by the DOJ, and one specifically credited a company for producing former employees for DOJ interviews. The ability of a company to provide its current and/or former employees for interviews with federal authorities may be directly related to the terms of employment agreements, employee handbooks, separation agreements, etc. Similarly, in light of the emphasis on punishment of culpable individuals as part of full remediation, it is important that employment policies and procedures offer a company the discretion to implement disciplinary and/or termination measures as necessary.

Promptness matters. The Revised Policy set forth in the JM requires self-disclosure to the DOJ “within a reasonably prompt time after becoming aware of the offense.”11 It further notes that “the burden [is] on the company to demonstrate timeliness.” While many of the above-refenced declination letters cited vaguely to the company’s “prompt” or “timely” self-disclosure, one letter specifically noted that the disclosure occurred within two weeks of the company’s board becoming aware of the misconduct. While this two-week turnaround is an example and not a rule, it sets an exacting standard for companies attempting to shoulder the burden of proving that self-disclosure to the DOJ was reasonably prompt.

Thorough investigations are paramount to success under the Revised Policy. Five of the six above-referenced declination letters specifically touted the thoroughness of the company’s investigation into the misconduct, and it is axiomatic that a thorough investigation is necessary to allow a company to satisfy the exacting qualifications for a declination. A sufficiently robust investigation requires a company to commit immediately to fully uncovering the truth, remediating any problems that are uncovered, and dedicating the resources necessary to do so. This may entail engaging the services of multiple law firms (audit committee counsel, company counsel, counsel for certain key individuals), a forensic accounting firm, a company specializing in foreign-language translation, interpreters for witness interviews of non-English-speaking personnel, forensic vendors to collect electronic documents and data, a compliance consultant, etc. Even if a company ultimately decides against self-disclosure, a commitment to the type of comprehensive investigation that will satisfy the standards of the Revised Policy is necessary from the outset in order to afford corporate decision makers maximum optionality when deciding how to handle the misconduct.

For additional information, please contact Ryan S. Hedges at +1 (312) 609 7728, Junaid A. Zubairi at +1 (312) 609 7720, Anthony Pacheco at +1 (424) 204 7773 or Joshua Nichols at +1 (312) 609 7724 or another Vedder Price attorney with whom you have worked.

1 https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/blog/criminal-division-launches-new-fcpa-pilot-program

2 Id.

3 Id.

4 https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-rosenstein-delivers-remarks-34th-international-conference-foreign

5 Id.

6 Id.

7 https://www.justice.gov/jm/jm-9-47000-foreign-corrupt-practices-act-1977#9-47.120

8 Id.

9 Id.

10 https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/corporate-enforcement-policy/declinations

11 https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/corporate-enforcement-policy